In 2018, Izabela Pluta went diving off the coast of the Japanese island, Yonaguni, where the Pacific Ocean meets the East China Sea in a stretch of powerful currents. Since that trip, Pluta has drawn on the physical experience of deep-water diving and its disorienting effects on sight, using it to influence her approach to perspective—both literally and conceptually. The sensation of being disoriented underpins the work currently exhibited at the UNSW galleries, under the title Nihilartikel.

Nihilartikel is the German word for the deliberate errors that appear in reference books, which indicate the work is a copy and—in the case of cheap music scores—avoid copyright infringement. They are, then, both markers of the distance between the original and the copy, and a form of evasion. I think of scores because that’s how I first encountered the phenomenon. Cheap, “unofficial” sheet music is frequently marked with ‘wrong’ notes that, if not corrected by the person using the score, create aural combinations of a distinctly different colour. Across Pluta’s work, these blue notes are used to play with the way the meaning—or weight—of images changes over time and to show that how we record something is always arbitrary and incomplete.

The exhibition is spread across three galleries and depending on whether you turn left or right when you enter, you’ll experience the show differently. The work that’s most haptic, and perhaps the easiest to access, is on the far wall of the left side gallery. This series, 26 Variations from Blue Spectrum and Descent (2020), is an arrangement of 26 cyanotypes made in response to a previous work, Apparent Distance (2019)—an installation displayed at AGNSW as part of The National: New Australian Art. That work, a large-scale installation of expanded photography, where images taken off Yonaguni were printed onto swathes of draped fabric, evoked the sensation and intensity of being underwater. In 26 variations, each of the 26 prints uses the cyanotype’s hallmark shadowy blue marks to gesture toward the lines and shapes of the installation, as well as the memory of the originating site. The work is both a documentation of prior work and new work—an example of how Pluta’s practice falls back in on itself. Many of her images respond to what has come before in a performance of photographic theory’s obsession with memory and reproduction. And while 26 Variations gestures back to Yonaguni, the site, now mediated through a series of displacements, becomes distant, shadowy. It haunts the image, but it is impossible to decipher. This doesn’t matter; the visual effect of the cyanotypes—the crisp edged curves, the moments where the blue shifts from brilliant to deep—is striking enough to encounter without the knowledge of the steps that led to them.

If it all sounds complicated and conceptual, it’s because the endless reworking and responding to site, image and memory that Pluta’s work performs is complex. Her images, particularly in this exhibition, are difficult to hold in the mind’s eye. They are endlessly slipping away, difficult to see no matter how long you look, always sending you back to the idea that perspective is impossible to fix and that tools like geography and cartography are incomplete and unreliable records.

Mapping and the arbitrariness of borders is explored across Iterative composition 1979 (pages 17--18 Australia) (2020), a series of prints made by contact printing maps from an out-of-date atlas to create flawed, unreadable reproductions that transform the maps from diagrams into a massed pattern of crisscrossing lines. If you’re alive to conversations about decolonising the archive, you might read the work’s gaps, its warps, shadows and clouded patches—its Nihilartikels—as tiny interventions into the way Australia’s landmass has been represented or mis-represented in Western cartography. For me, that’s too much of a stretch. Instead, I found myself thinking of the way their overlapping, textured surfaces create an impression of skin, turning a diagram of the earth back into a textural, tactile image of its surface. The earth or an elephant. Skin, anyway.

I needed to imagine this relationship to the physical in order to find a way in to the series because Iterative composition and the smaller contact prints like Glaciers, dunes and prairies with a dust storm approaching (2021)—made from pages of an early edition of The Penguin Dictionary of Geography, and displayed in the moody, right-hand gallery—feel closed off, as if the march of mechanical reproductions has led the image to a kind of stale endpoint. These images of images are difficult to grasp. This isn’t a criticism—the airless quality feels like the hermetic vibe of the past two years, where a once open mindset toward space has become contained.

Analogue photography has always had a split outward/inward personality—you go out into the world to take photographs and then return to the enclosed space of the darkroom to bring them to life—but here the enclosed space, the workshop, feels all absorbing. It’s there in the shallow depth of field of the contact prints and the abstract space of the cyanotypes, and it’s there in the blinding light streaks of Crepuscular rays (mechanical reproduction) #6 (2019), two black and white images made using a photocopier. It works in some ways to evoke the disorientation of a dive, but it also works to keep you, the viewer, at a distance, to disorient you conceptually, to make things difficult to hold.

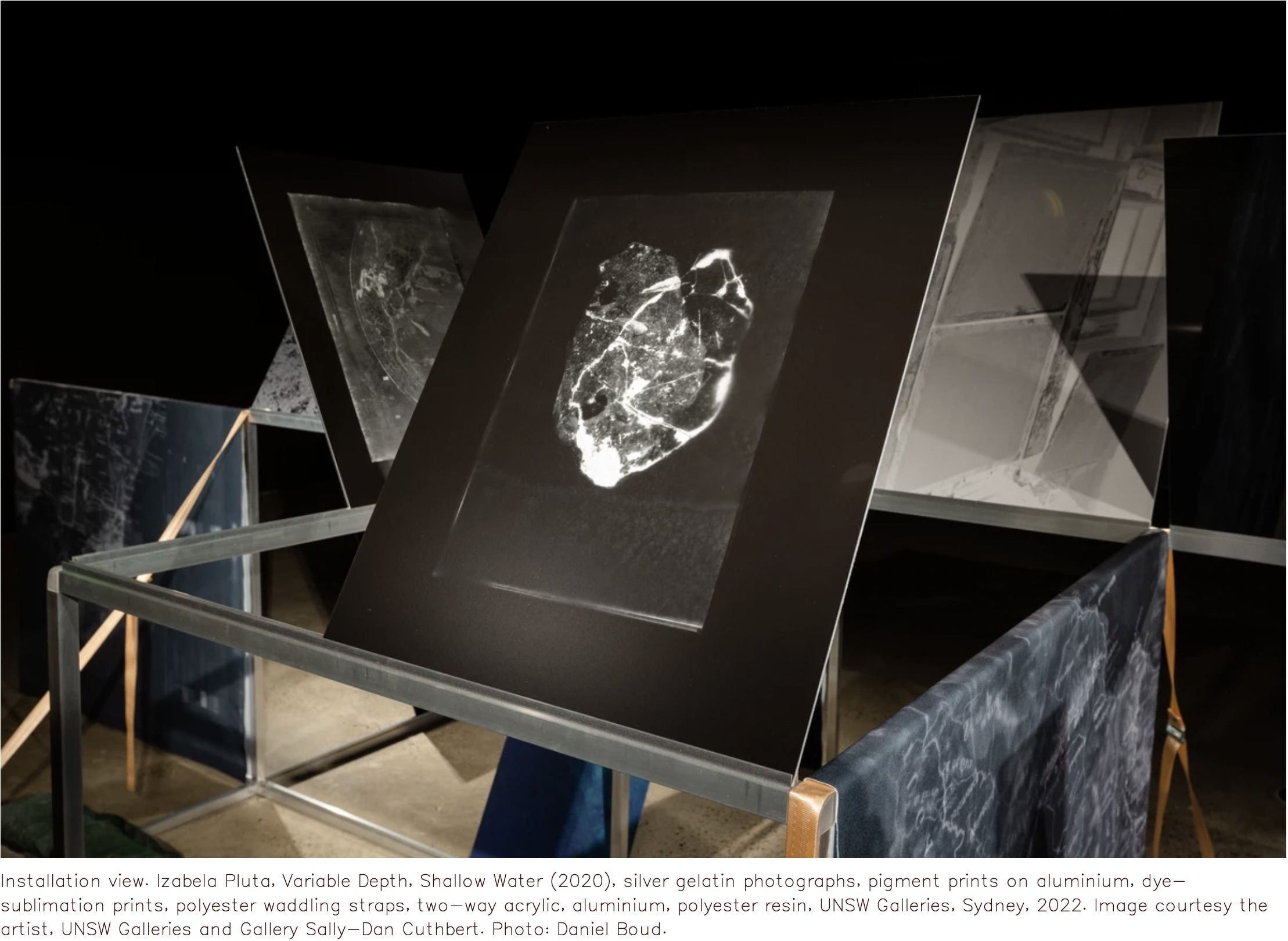

We can never see everything. Partial views, as well as the interplay of surface texture and smoothness, shape the installation Variable Depth, Shallow Water (2020), originally installed at Spazju Kreattiv in Malta in 2021 and set here in a darkened room alongside Apparatus (2020). Variable Depth, Shallow Water responds to The Azure Window, a collapsed sea arch off the island of Gozo, Malta, which Pluta visited in 2019. The limestone ruins lie twelve metres below sea level. The images—a collection of spattered surface textures drawn from corrupted drone footage, maps and clouded scenes of sea and rock—are displayed on a metal frame and interspersed with blank plates and mirrors, angled like the reflex mirror in an analogue camera. The structure is large enough that to look at the work you have to walk around it, physically changing your perspective as you peer up or crouch down. One of the mirrors reflects the bubbled surface of the gallery roof, putting you back into the space of the gallery. It’s impossible to see the whole thing at once.

A short list of perspectives, as if seen through a viewfinder:

1. Close up. Mottled cloth.

2. Medium shot. Your own face, reflected.

3. Wide shot. The whole room, parts of the structure hiding other parts. Corners dark, receding, your eye drawn to a bolt of light where the overhead lighting hits a shiny, metal plate.

4. Shots where the foreground obscures the background, blurred shapes behind sharp lines. Shadow.

One way of looking at Pluta’s work is as a performed theory of photography. As an example of praxis, it is sophisticated and thoughtful. Through process, she thinks about the camera as both an instrument of imperialism and as a more intimate tool for recording memories, always incompletely and unreliably. This can be difficult to grasp in the moment. I struggled to get my bearings and to find a way into the visual experience of the work. And, because the show includes only one photograph of a physical site, it can be difficult to contextualise the works on display. I suspect that because of this, the exhibition speaks mainly to an audience of people who are already deeply engaged in theories of photography. For them, this is a rewarding show that cracks open thoughts about the tactility of image making, the depth of sight, and the role of photography in the process of remembering, imagining and re-imagining the world.