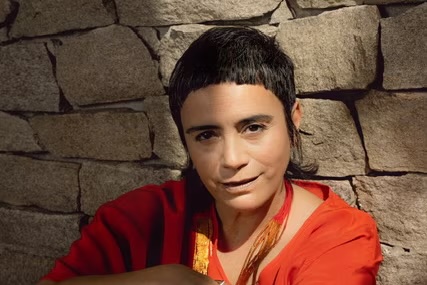

When Lisa Reihana walks through Voyager, her newly opened exhibition at Ngununggula, she doesn't see her works even as they literally unfurl and move across the walls. To the highly acclaimed Aotearoa artist, these time-intensive, technically complex, visually mesmerising works that span video, installation, sculpture, photography and costume design, are just artefacts.

"These are the flotsam and jetsam that come out of the conversations and the people that I meet," she says, half-jokingly, of the work at the Southern Highlands Regional Gallery. "A lot of these video works take a lot of time and energy and require so many communities of people and cast and crew. Walking through the galleries is like walking through space and time."

This new survey of works made since 2018 continues Reihana's interest in storytelling and revisioning colonial histories, addressing the ongoing impacts of colonisation on representation, identity and our understandings of community and place.

Recasting history for new perspectives

In these latest works, Reihana casts Maōri ancestor Tangi'ia, Earth Mother Papatūānuku, models from the studio of the late New Zealand sculptor William Trethewy, and several 19th century Chinese goldminers at work in Otago.

Arguably one of the more well-known characters is Captain James Cook, whose death is just one of the myriad stories presented in her sprawling tableaux In Pursuit of Venus [Infected].

This large-scale, live-action, eight-minute film is a sly, visually gorgeous, celebratory reclamation of the stories implied and untold in Frenchman Joseph Dufour's colonial, nineteenth century, panoramic wallpaper, Les Sauvages de la Mer Pacifique (The Native Peoples of the Pacific Ocean).

In Reihana's version, problematic Enlightenment-era imagery is exchanged for scenes of cultural practice, dance, community gatherings and cross-cultural exchange, with Māori, Pasifika and First Nations Australian people thriving and accounted for. The work, which is represented in Voyager by a large photograph, was a major highlight of the 2017 Venice Biennale.

For Reihana, who is of Ngāpuhi, Ngāti Hine, Ngāhi Tū descent, its popular and critical reception has led to numerous international commissions and exhibitions.

But it hasn't been without its challenges. "It's fantastic to make a really great work but it's also a rod on your back, because everyone has a touchstone [now] and they want more of that and I don't want to repeat things," she says.

"They have to have a reason to be created again. I've only got one life and I need to keep moving."

But for Reihana, the technical skills required to make these virtuosic works are the easy part.

"The relationships are the hardest bit but they're also the best bit," she says.

Navigating relationships

Reihana says telling cultural stories can be fraught, which is why collaboration and giving time to projects is central to her practice. There's also a lot of joy and, occasionally, a bit of matchmaking. "Sometimes I've cast people because I want them to meet each other, because I think they would get on and then go off and do something else themselves," she

In IHI (2020), she cast New Zealand choreographers Nancy Wijohn and Taane Mete in her retelling of the Māori creation story, bringing them back to dance together for the first time in 20 years.

"I knew they were great friends and to have that sense of care and love displayed between these different stories was something that I wanted to explore," she says. Other times, it's all about research and locations. GOLD_LEAD_WOOD_COAL (2024) was first made for Hong Kong's Tai Kwun Contemporary and, in wanting to create a work that connected Hong Kong and China with Aotearoa, Reihana took the story of the British cargo ship SS Ventnor as her point of departure.

Shipwrecked off the coast of New Zealand's North Island in 1902, it was repatriating the remains of 500 Chinese goldminers to Guangdong when it hit the coast and sank.

Reihana expands the story to focus on the rituals and care of the local Māori community, who collected and buried these washed-up boxes of bones.

"I wanted to look at that care, how humans care for each other; the Chinese miners looking out for each other in the face of a lot of racism and the care that Māori had for these Chinese bones when they found them on the shores," she says.

Across three expansive walls at the gallery, interior scenes, moody landscapes, calligraphic writings and rich fabric textures cross-fade and overlap, connecting Otago's rugged goldfields to opium dens, to the northern Aotearoa shores and Māori locals, to the female victims of the Opium Wars held in the prison that once sat on the site of the Tai Kwun arts precinct.

A work about belonging

In making work specifically for Ngununggula, Reihana hoped to collaborate with local First Nations cultural custodians and community members.

However, pandemic-complicated timelines and logistics made that tricky.

Instead, she drew on conversations with the daughter of late local elder Aunty Velma Mulcahy, who gifted Ngununggula its name, which means "belonging" in the local Gundungurra language.

"I was thinking about that naming and how she talked about it as being a safe place for creativity and for people coming together and for community," Reihana says.

Reihana's Belong (2025), which adorns the entire front facade of the building, is a dazzling pink, orange and black wall of shimmering pixel-like discs that murmur and shimmer in the wind. The zigzag design draws from the patterns found at the top of woven kākahu, or Māori cloaks. Reihana knows first-hand the importance of belonging — of crossing thresholds — and of being welcomed somewhere.

Māramatanga is the first work to greet you once you've passed through Belong and entered the galleries. It was commissioned by Reihana's alma mater, Auckland University, and was another collaboration, this time with students from the university's dance program, which didn't exist when Reihana was a student. "As a young urban woman looking to learn about my culture, because it was so stamped out, it was very hard even to learn language," she says. "You couldn't find it in our English education system. It was a real milestone moment when the university finally capitulated and decided to build a marae, or meeting house, for all the Māori students, and for the wider university."

On finding your place

That experience, as well as the opportunity to meet the master artisans who carved its interiors, rich with depictions of Māori ancestors and navigators, continues to be formative for Reihana.

"We talk about the meeting house as being your Tūrangawaewae, your place to stand. And wherever you stand [with the carvings behind you], you've got the protection of your people behind your back," she says.

For Māramatanga, Reihana invited the students and several older friends to take inspiration from the figures in the marae, as well as their own ancestors, and to reflect on what they might look like for themselves within a contemporary choreographic video piece.

One of the dancers, Yin-Chi Lee, spoke of her experiences as being part of the Chinese diaspora and feeling landless; a constant guest in other countries. Using green screens, Reihana suspends her in the open sky.

"She feels landless and unbound. So it's about taking these ideas and trying to translate them in a way that still is poetic but that gives somebody a place to be."

Other vignettes capture dancers-as-ancestors against hypnotic, kaleidoscopic backgrounds of ocean, forest and mangroves.

These mesmerising visuals define all of Reihana's work, whether she's retelling Māori ancestral stories or re-writing colonial histories. Their uplifting beauty is another strategy — an invitation for viewers to lose themselves in the stories and perhaps re-emerge with a new perspective or appreciation. "I'm bringing something of my world — and other people's worlds — and I'm re-showing them in this space and it's a real gift [to be able to do that]," she says. "I think the politics today is just so weird and so scary. So I think having all these different cultures and people together says a lot."

Lisa Reihana: Voyager is at Ngununggula, Bowral, until November 9.