Textiles are having a moment. Internationally, the revisionist survey

Woven Histories: Textiles and Modern Abstraction is touring the United States, wrapping up at the Museum of Modern Art in 2025. Earlier this year, textile works garnered record high water marks in the American art market despite being a category considered “hard” to collect and conserve.

[1] In Europe, the Venice Biennale was flush with the medium. As critic Jason Farago quipped in his

New York Times review: ‘The show is remarkably placid, especially in the Giardini. There are large doses of figurative painting and (as customary these days) weaving and tapestry arranged in polite, symmetrical arrays.’

[2] Farago’s statement is not just fatigue over curatorial formulas, but nods to the passé assessment that textile practices have historically accrued, and that artists have worked hard to beat back over, at least, the last three generations.

Closer to home,

Art Monthly Australasia published

The Textiles Issue in winter, canvassing a groundswell on the subject, and the 11th

Asia Pacific Triennial in Brisbane is brimming with fibre and weaving. The National Gallery of Victoria’s (NGV) 2023

Triennial also featured major textile works and fibre art commissions, including the 100-metre long pandanus weaving

Mun-Dirra (Maningrida Fish Fence) (2023), made by thirteen Burarra women artists working collectively out of the Maningrida Arts Centre.

[3] The NGV can trade on

Mun-Dirra being

‘the largest woven sculpture ever produced in Australia’,

[4] but the more compelling scale is the genealogy of weaving that far eclipses the ebbs and flows of taste. 2023 marked the 5

th Tamworth Textile Triennial,

Residue + Response: Connecting histories and futures, which featured a record number of artists.

[5] And earlier this year, the National Gallery of Australia staged

A Century of Quilts, centred on

The Rajah Quilt (1841). Made by women aboard the HMS Rajah convict ship, the quilt is (unexpectedly) the gallery’s most requested work of art.

[6] Despite its popular status with the public, and the exhibition having been staged under the

Know My Name banner, there is a dearth of institutional publishing on the artists/makers (unattributable women lost to history) or on the reprisal of quilts from social history to art — more categorical glitches.

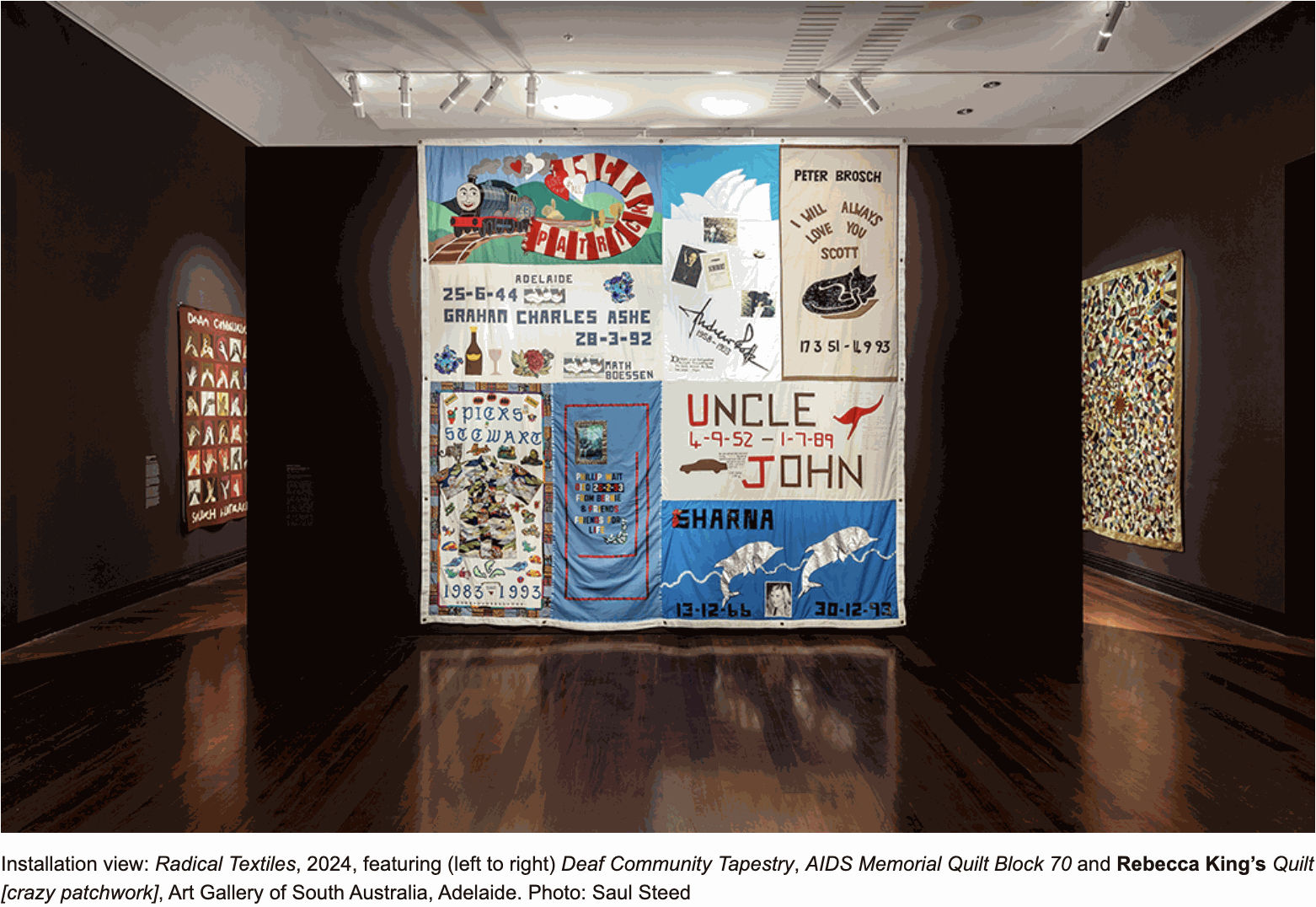

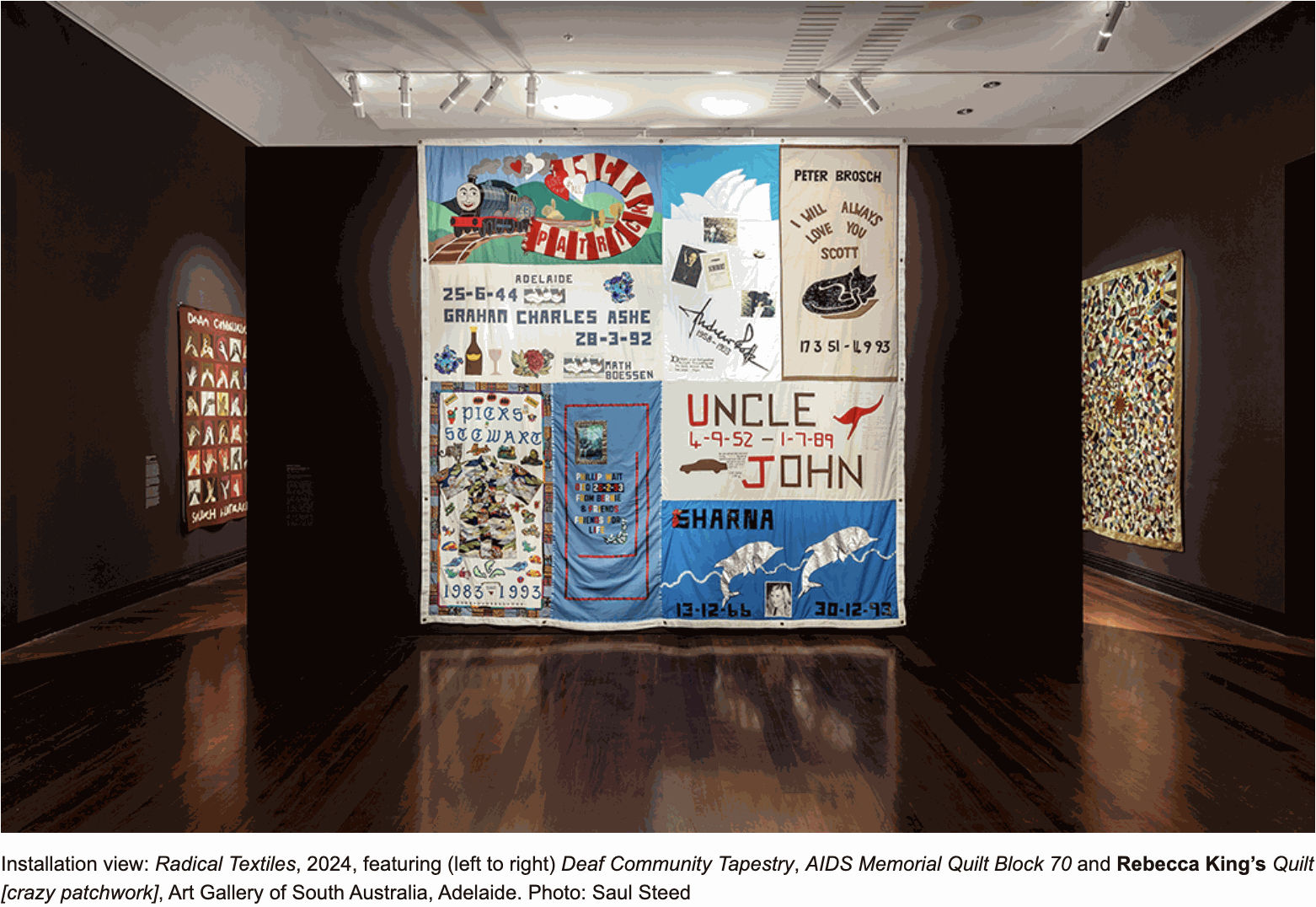

This summer, the Art Gallery of South Australia (AGSA) has picked up the gauntlet with Radical Textiles. Featuring over 100 artists, designers and makers, working across tapestry, embroidery, cross-stitch, fashion, lace, knitting, quilting, appliqué, installation, soft sculpture and socio-historic artefacts (South Australian premier Don Dunstan’s pink shorts are an iconic inclusion), Radical Textiles sits dead centre at the crosshairs of its titular remit. Its aim is mirrored in a curatorial collaboration between Rebecca Evans, Curator of Decorative Art and Design, and Leigh Robb, Curator of Contemporary Art. Four years in the making, Radical Textiles took shape while the evolving forms and historical significance of textiles have been under close scrutiny.

Located in AGSA's underground galleries, the ticketed exhibition opens with a floor to ceiling hang of Australian trade union banners, the room painted propaganda red. These objects orient us to the curatorial inclusions and exclusions of the show. There is a productive boundary around the medium itself; you won’t find any fibre art or basketry here, no Mun-Dirra’s. And, as a meaningful contribution to this broader, unfolding revisionism, Radical Textiles centres South Australian stories and practices in its arc.

A parallel motif to the Rajah Quilt, the trade union banners have been lifted from the halls of social history. Individually, they are portals onto the changing commonwealth of Australia which bookend a 150-year timespan to play out the compulsions and shifting concerns of textile artists and practices up to today. They also draw out one of the many genealogies within Radical Textiles — a set of inherited or transposed skills, specifically needlework from Europe, which artists Kait James and Sera Waters usefully disrupt. En masse, the repeated iconography of the banners—justice personified, scenes of labour and sovereign insignia—manifest a socio-aesthetic experience. Their ribbons of festooned mottos play out the shared etymology of ‘text’ and ‘textile’: textere, meaning ‘to weave’. Kate Just’s opposing suite of knitted paintings pulls this thread into the twenty-first century with her viral placard slogan: ‘I can’t believe I still have to protest this shit’.

While a vitrine presenting works from the 2020 Stitch & Resist project (produced through Adelaide’s Centre for Democracy) hits all the craftivist notes, the more ambiguous objects in the same room are several unattributed crochet pieces spanning both World Wars. Featuring silhouettes of Australia emblazoned with ‘Our bit’ and ‘The Aussies and the Yanks are here’, they are as overtly political as they are domestic (bordering on gauche in this contemporary context). Success to the Allies (1917), with its decorative edge of weighted red beads suggests a prior life as a jug cover used to keep out the flies. From the small handmade quotidian object comes a big story of Australia’s shifting tidal allegiances and patrolled borders and the compulsive conviction for sloganeering.

The ensuing galleries capture an energy field of making dedicated to time, the singularity of an artist’s hand, objects made collectively or thwarting authorship altogether, the intergenerational and trans-historical, and the embodied politics of these material phenomena. The northern end of gallery 25 sees a powerful head-to-head between Fiona Hall’s All the King’s men (2014-15) and Pierre Mukeba’s For Sale (2017). Hall’s military uniforms, knitted into bodiless neo-tribal characters, meet the confrontational gaze of Mukeba’s reclined limbless figure. Here, appliquéd kitenge—the patterned West African fabric materially loaded with colonial trade routes from Indonesia to Denmark to Africa—is Mukeba’s shorthand for painting. The Indonesian wax resist technique is reiterated in Emily Kame Kngwarreye’s Batik shirt (1984), hung high on the same wall, a welcome reminder of Kngwarreye’s aesthetic development as she worked in batik for a decade before turning to painting.[7] Hall and Mukeba’s antagonisms ricochet around the room: in the ecological exorcisms of Sera Waters’ Storied Sail Cloths (2021-22) and Lara Tilbrook’s Duty of Care (2020), and the nuclear imperialism of Narelle Jubelin’s petit point Surveyor, Woomera, South Australia (1989).

The southern end of the gallery shares this dynamism, but with a tonal shift to the devotional. At its centre is

Every face has a story, every story has a face: Kulila! (2016). The installation of nine soft sculptural self-portraits by Yarrenyty Arltere women artists,

[8] materialises a central proposition—kulila, to listen—and counter strategy to the machismo of

All the King’s men. ‘That’s what we do, sew and talk and listen and try to make things get better.’

[9] Kulila’s social practice also reverberates around the room in Nell’s

NELL ANNE QUILT (2020-24) and the

AIDS Memorial Quilt Block 70, made in the early 1990s. Fueled by respective crises (Nell embarked on her project during the onset of Covid), they are embodied tributes to invisible lives, loved and lost. Here, close viewing is close listening.

Adjacent are Kay Lawrence’s twin tapestries marking one hundred years of women’s suffrage in South Australia—another compelling transplant from the halls of power—which segue into gallery 23, a room dedicated to tapestry. There is an equalising mix of South Australian and international artists, including Morris & Co., Kiki Smith, Pru La Motte and Sonia Delauney, yet the medium appears siloed, likewise in the exhibition’s closing purpose-built fashion room. But as it opens back up onto a psycho-sexual seance between

Sarah Contos Presents: The Long Kiss Goodbye (2016) and

Guardians (2014-16)

by Tarryn Gill, the energy field vibrates once more. At the southern end of gallery 22, a call back to kitenge is found in Yinka Shonibare’s

Refugee Astronaut (2015); Eko Nugroho’s reworked social realism finds new form in his suite of machine-embroidered wall hangings; and Sally Smart’s theatrical installation

Performance/Punokawan/Chout (The Choreography of Cutting) (2017) uses the sister medium of collage to push textiles into the expanded field. Collectively, these works are ‘semionauts’,

[10] sign-travellers, made by artists who materialise trajectories between things.

In the Radical Textiles catalogue, Paul Yore writes about his work Let us not die of habit (2018):

My appliqued quilt…is like a web that has been cast across the wasteland of culture, catching all kinds of flotsam and jetsam upon its surface, ensnaring multiple possible meanings… Its declarative title reveals the core reason I make art: the needle and thread necessitate a slow thoughtfulness, their preindustrial logic offering a counterpoint to the distracted immediacy of digital culture, with its swiping, scrolling and clicking into oblivion.[11]

Yore’s quilt hangs adjacent to the semionauts and is a powerful somatic invocation of doomscrolling. It is also a helpful signpost in the rising trajectory of textiles. ‘Pre-industrial logic’ is present across the revised and re-visioned practices of

Radical Textiles, offering us a counter-aesthetic to the metaculture of today. As described by American academic Anna Kornbluh, author of

Immediacy: or, The Style of Too Late Capitalism (2024), our moment is characterised by directness and literalism, or instant uptake: the straight-to-camera confessional of reality TV, the decline of third-person fiction and the rise of memoir, or the multi-sensory immersive experience of

Van Gogh Alive, as opposed to an encounter with the painting

The Starry Night.

Flight from mediation is the latest in a grand sweep of de-materialisations and signals the long tails of relational aesthetics. In today’s art world, the ethics of making is frequently the object of contemplation; personal biography is subject. But as Kornbluh argues, something is lost in this renunciation of form. There are political benefits to opacity, to slowness, to metaphor. It can help us to think abstractly, plurally; to ‘represent what the collective good might be, or what the collective good should be’. After all, ‘sewing is a craft about bringing things together’.

Moralising the aesthetic shifts of too-late capitalism is a bigger subject than this review—or any single exhibition—but recasting textiles as one of many possible counter-aesthetics to a fractured, dispersed present is a compelling proposition. While the radicalisms of Radical Textiles are equally dispersed—from social history to sexual liberation to ‘talking back’ to power to formal ruptures with the past—the exhibition remains radically material.

In the same room as Kulila, Kay Lawerence’s tapestry Rant (2002, 2009 and 2017) hangs high on the wall. Woven in three phases spanning fifteen years, Lawerence lifted passages from her teenage diaries—particularly vitriol aimed at other teenage girls—to create a six-and-a-half-metre-long repentance. It seems an easy categorical leap to read the work as ‘first-person confessional’, but the sunken time and labour of Rant—it's medium—makes it a powerful meditation on hate or living with your ghosts. Rant begs for close reading, long looking, solidarity with an audience. It is an endurance exercise in self-forgiveness. Or, as the Yarrenyty Arltere women say, ‘That’s what we do, sew and talk and listen and try to make things get better.’