What’s your personal connection to flowers?

My particular interest within my arts practice is focused on the reproductive organs of plants and the by-products of plant reproduction; fruits and seedpods.

Flowers are the reproductive part of plants; their primary role being to attract pollinators to reproduce. I’m inspired by their sheer ingenuity and tenacity, the clever methods they have evolved to achieve pollination, their complex symbiotic relationships with insects, birds and mammals, and the defence mechanisms they have devised to repel and ward off parasites and predators. They are signifiers, forming at varying times throughout the year according to weather and geographical conditions.

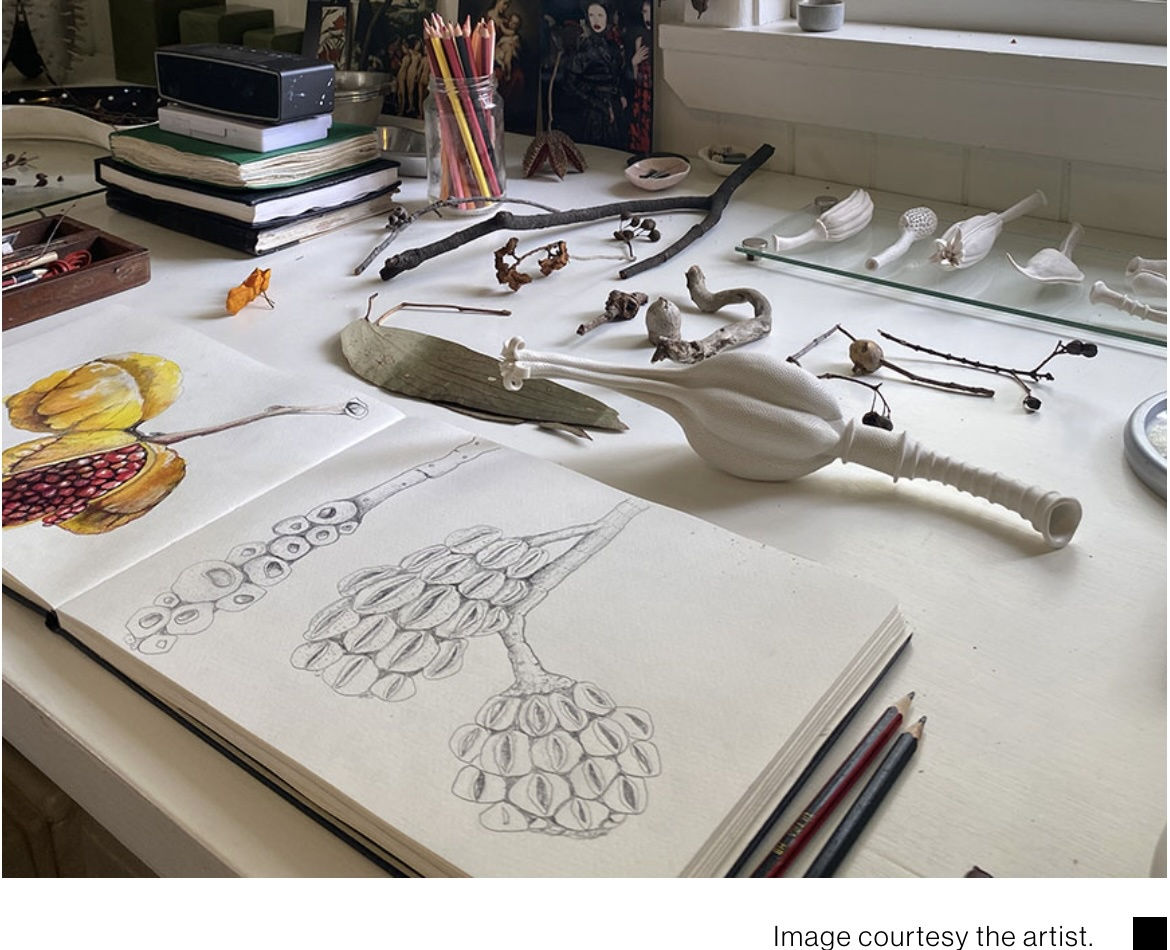

I live and work on protected native bushland in Wootha, Jinibura Country in the Sunshine Coast Hinterland. We (my husband Jeff and I) have planted a full native garden around our home on what was once open farmland. My studio desk is always covered with native flowers and seedpods from the garden and bushland, I surround myself with source material inside and out.

Close observation of this natural environment has led to a fascinating world of tiny, intricate and complex organisms, the understated and overlooked in hidden spaces and places. I closely watch flowers metamorphosise through pollination to seedpods, I study and examine junctions, joins, form, texture, cracks and crevices and the way layers peel back to reveal sensuous interiors.

Flowers play a vital role in my arts practice; they instil a sense of wonder and joy and play a significant role in the ongoing cycle and ultimate survival of the natural environment.

White and almost bone-like in their final appearance, my porcelain interpretations of the natural environment are like ‘flowerbones’. This is the collective word I use to describe my sculptural artworks. I spend a lot of time bushwalking, observing and collecting. I arrange collections of seedpods, flowers and plant material and look at their relationships to one another. I sketch, documenting distinguishing features of interest, and then I begin to make sculptural forms.

Starting with basic shapes created in clay, these initial rudimentary forms are like my rough sketches. I then allow the clay to dry enough to begin carving back into the form. Slowly the pieces take shape. Most works are constructed in two or three pieces to obtain the detail required then joined towards the final stages of the making. Some shapes are filled with individually hand rolled balls of clay or tiny floral shapes and each piece is laboriously yet lovingly covered with tiny pin holes. The work is slow, contemplative and meticulous in its construction. This repetitive process of rolling, pinching, carving and dotting is both mediative and a form of honouring my subject matter. Nature is slow and deliberate. The pieces are small and intimate, held and shaped within the curves of my hands and fingers. My relationship to my materials is intimate.

Once completed the sculptural forms are dried very slowly in polystyrene boxes for up to four weeks to prevent cracking (hopefully). Nothing about my process is instant. At any point the work can crack and break. As careful as I may be, it’s out of my control in many ways.

When fully dried, I finish the work with two to three coats of terra sigillata and fire them slowly in a small kiln to approximately 1100 degrees Celsius. Whilst I have an idea of how the works will sit together during construction, the final installation of the finished artworks is not fully resolved until all pieces have survived the firing process. Nothing is a given.

It’s a combination of all these things. It may be how a flower bud hangs from a small branchlet, the growth rings of a Casuarina leaflet, the way outer petals shrivel around a developing seedpod. The differing male and female internal structures within a Brachychiton flower, the joy of a bright orange peanut tree seedpod bursting to reveal shiny black seeds. I am continually informed and inspired by what I observe.

Porcelain has long been used to create conventional equipment and scientific tools. What is it about the history of this material that attracts you? Is it a conceptual choice or more about the aesthetic qualities of porcelain?

Porcelain has a rich history of being desirable and precious which correlates perfectly to that of my subject matter: they simultaneously possess qualities of fragility and strength.

The innate qualities of porcelain play an important role both aesthetically and conceptually within my practice. To begin with it’s a smooth, quite seductive material to work with, it’s a little temperamental and needs slow careful attention. The purity, whiteness and almost bone-like quality of the media of porcelain highlights the textural qualities of the objects I create. The silky satin finish of terra sigillata (also made from porcelain) hugs the curves of each form and when hung upon the wall on a white surface: white on white, void of colour, the objects don’t disappear they pop from the surface, all details illuminated with shadows accentuating the shape of each object. All these aspects are important in the final presentation of my artworks.

I am drawn to the aesthetics of museum display: glass cabinets filled with curios objects, as well as scientific equipment: hand blown glass vessels, porcelain crucibles, funnels, mortar and pestles, and laboratory beakers. These objects form part of my many collections of objects and feed directly into my practice.

You’ve created a number of ‘flowerbones’ inspired by various ecosystems from Noosa to Tasmania. Were there any specific aspects of Brisbane’s native flora that captivated or inspired you in a unique way?

‘Flowerbones of Meanjin’ is the title of the work I created for Rearranged: Art of the Flower. When I was asked to participate in in this beautiful exhibition it was important for me to highlight the rich and diverse native flora from within this region, Turrabal and Jagera Country. Deciding which species to work with was a difficult decision, there are so many incredible plants native to this subtropical region. My selection tended towards those I knew well, plants I had encountered bushwalking and street walking in Meanjin (Brisbane). Whilst much of the original vegetation of the city centre has now been diminished, Brisbane boasts a wide variety of beautiful native street trees. Upon my many visits to the city centre, whilst others crunch seedpods and fallen flowers under foot, I collect them filling my pockets and handbag with these beautiful treasures. This collection makes its way back to my studio inspiring new pieces.

The native plant species which inspired and informed the work for the exhibition are as follows:

- Brachyciton discolor, common name: Lacebark tree.

- Melaleuca viminalis, common name: Weeping bottlebrush.

- Casuarina cunninghamiana, common name: River sheoak.

- Ficus coronata, common name: Sandpaper fig.

- Pittosporum revolutum, common name: Brisbane laurel.

- Parsonsia brisbanensis, common name: Brisbane silkpod.

I respectfully reference these plants of Meanjin and acknowledge their cultural significance to the Traditional Owners.

Your porcelain studies portray the process of ‘gynoecium’. Can you describe what this process is and why it’s important for Brisbane’s ongoing biodiversity?

The word ‘gynoecium’ comes from ancient Greek meaning ‘female house’ and is a collective term for the female parts of a flower that produce ovules and ultimately develop into the fruit and seeds after pollination.

As mentioned earlier the symbiotic relationship of plants with insects, birds and mammals is complex and vital for pollination and plant reproduction to take place as is climatic condition. Despite their resilience it’s a delicate balance and with continued urbanization, land clearing, development and changing climatic conditions the balance will be tipped, affecting the ongoing biodiversity of the region.

Ficus coronata (Sandpaper fig) which I have based work upon for the exhibition is a particularly good example of the symbiosis between plants and insects. One cannot survive without the other.

The fig tree is unique because its flower, made up of hundreds of tiny florets, is wrapped inside the fruit. The coronata produces a fleshy, un-ripened fruit that can only be fertilised by a corresponding species of wasp. The female must push through a small opening in the fruit, losing her wings and antennae in the process, to reach the flowers inside. The wasp then lays her eggs inside the fruit before dying. When they eventually hatch, the wingless male offspring bore their way out, clearing a path for the young female wasps to carry the mature pollen to another tree of the same species. Carbon dioxide is subsequently released through the opening made by the male wasps, allowing the fig’s fruit to ripen.

In an era of growing climate uncertainty, your work encourages wonder and curiosity about the planet we share. How do you believe art, and specifically your ‘flowerbones’ sculptures, can play a role in inspiring a sense of connection to our natural environment?

By sharing my interpretations of the world around me through my arts practice my hope is that I may: inspire others to look more closely; instil a sense of wonder in the natural world; create awareness of how important it is to protect, respect and care for Country; and encourage others to learn more about native Australian plants.