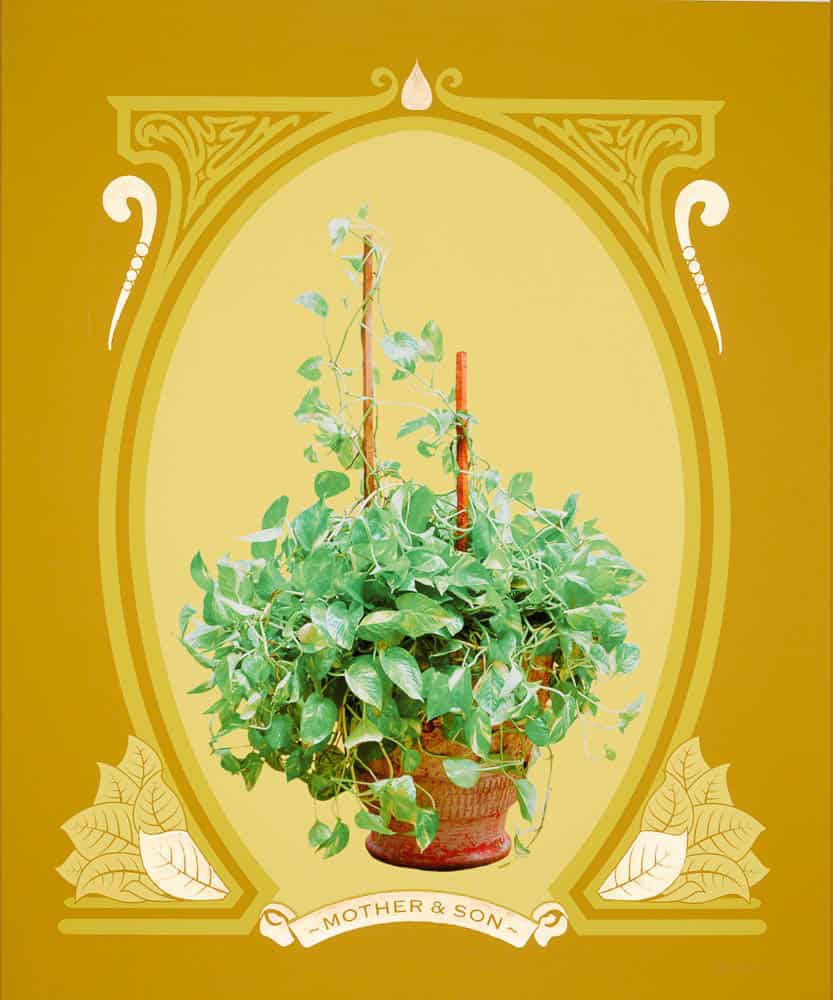

His mother’s ledger and her diaries appear in his body of work titled Substitute: The Untold Narrative of a Mother and Son. His mother is an important inspiration in Substitute, a mixed media work with the image of a money plant (Golden Pothos) at its centre.

“The money plant is a substitute for her offspring, who have left home. She nurtures the plants as if they are her children,” Syed says.

In his studio, we talk about banknotes which are a prominent device appearing in many of his works. Substitute, Currency of Love, Capital Couture (Sherwani) and his Divine Economy series, which Flying Rugs included a miniature rug made from whole banknotes stitched and fringed with shredded banknotes, all make use of currency in different ways. His work engages with the central role that money plays in economies of consumption and how money often navigates cultural and political identities, historical milestones and power structures.

“The one US dollar played an important role in my exploration of the concept Divine Economy. Almost 28 years after the release of the current iteration of the one dollar bill, American lawmakers added the phrase “In God We Trust” to the banknote in an attempt to demonize and claim moral superiority over the communist Soviet Union during the Cold War…the primary purpose of money is to project religious identities, bolster preconceived notions of moral superiority, and to measure ownership, economic power, and ultimately false prosperity.”

Syed stands excitedly from behind his desk and walks to the cupboard to show me the notes he has collected. Some of them are in envelopes held in bunches, donated by friends and given by collectors who no longer want them. He also avidly collects banknotes still in uncut sheet form, and others meticulously shredded and ready to be used for his projects. His interest in currency brings us back to the topic of his parents and the connection between currency as a device and a deep link to the memories he has, of his father who collected coins, stamps, and paper currency from across the world and of his mother counting the wages each month.

In Discourse Within Discourse: The Circle his mother, Azra, plays the role of collaborator. Syed learnt new skills from her about dye and spices to create a work which evokes the senses of sight, smell and taste. It’s his first installation showing seven spices encased in fragrant dyed cheesecloth suspended with the use of traditional Zardozi embroidery threads from Pakistan. The installation pays homage to Suspended Stone Circle II by Ken Unsworth.

Upon seeing Unsworth’s work, Syed says, he “felt gravity didn’t exist…the stone must be very heavy but it is not…this was one of the few artworks that nudged me towards art making, or more precisely installation art.”

Syed’s Circle is an antithesis to the post September 11 world, a world obsessed with fear, of terrorism, of islam and of the different ethnic minority groups residing within America. A world where the popular cultural discourse propagated the idea that America is a melting pot.

“I am absolutely against that idea because melting pot means you are making a homogeneous mixture, that things have no identity of their own, everything becomes a gooey mess. To me America should be an amazing Biryani where every grain is different,” Syed says.

During this time his work was being seen to engage in postcolonial discourse with spices from Pakistan being seen as a statement against colonialism. It is the first time he felt his identity as an artist dictating the interpretation of his work. “Nobody would consider me an American artist or a Western artist, they would look at me and the works…and say it always goes back to my South Asian heritage”.

He does not start his creative process from an idea centred around his heritage but uses aspects of his heritage and personal history as a tool to make his art. This practice, he has learnt, can pigeonhole him when viewed by Western eyes. Herein lies the challenge as Syed exists (like my own experience of the migrant diaspora), in the nexus between the two universes of his heritage culture and his adopted home, not fully occupying an identity in one or the other. When he goes to Pakistan, he is seen as an artist with Western sensibilities rather than Pakistani and when he is in the West he is viewed as a Pakistani/Muslim artist rather than a “Western” artist.

Abdullah Syed, Sherwani (Capital Couture series), Hand-folded uncirculated Pakistani rupees and staple pins, Installation dimensions variable, Image courtesy the artist, Photography by Mahmood Ali

A borderless nomadic existence between Sydney, Karachi and New York, a life dedicated to the quest for learning and mentors, rich with creation and creativity suits Syed. From a young age, he sought this existence and worked to make it real. “I grew up with the idea that, for knowledge, travel as far as you have to,” he says.

I sense a humble reverence towards his past mentors, as Syed talks of those who helped him along his path. The stories bring to my mind an image of Syed as a Sufi disciple with his master leading the way on the path of devotion. His mentors helped shape not just his art and design practice but his confidence and approach to life as a person and he seeks mentors and teachers wherever he goes.

One of people who is currently part of his life and whom he admires in his local community is Khaled Sabsabi, an award winning artist from Western Sydney, where Syed has been living since 2006.

“Brother Khaled Sabsabi [the founder of eleven Collective] wants to make sure that migrant artists are well represented, taking their narratives as their own and not as tokenistic artists. He wants us [the members of eleven Collective] to genuinely talk about our issues as artists from the Islamic diaspora. Not all muslim artists are the same … and have our own agency and that is what eleven is about”.

During his time with eleven Collective which includes other artists from migrant and muslim backgrounds, Syed exhibited works such as Soft Target. In Soft Target Syed stands on top of a printed plastic mat which is a bullseye target that is placed in front of famous tourist attractions around the world.

“In military terms, if you destroy soft targets, it’s the thing that brings the people’s morale down as the landscape they were used to has changed. By putting myself in front of the soft target location or tourist attraction in a docile manner, not even looking at the camera, I pose the question of who is the soft target here? Is it me? When you stand in front of this artwork there is a moment when you replace me and you stand in it as a target. It was a risk I took as part of my political activism work that is based on empathy and sharing vulnerability. If I perform this work now, I will probably get into serious trouble. I don’t know what courage I had…”

Later this year Syed will present at exhibitions in New York, Sydney & Melbourne. In Sydney visitors will see his vision and courage on display around the question of How to: Democracy at the Campbelltown Arts Centre.

For the exhibition Syed will create “paper dresses” with the words “Fair Dinkum” printed on them as marketing slogans. The concept of paper dresses is inspired by a short-lived fashion novelty trend of making clothes from disposable paper fabric in America in the 1960s and later used for the former US President Richard Nixon’s campaign in 1968.

“The rights of people being encroached for example on Manus island, is that a fair go?” Syed says, questioning if the concept of Fair Dinkum is true for all Australians today.

“My practice is a pendulum which is between politics and spirituality. Right now my focus is on politics. The work to be exhibited will be my take on democracy.”

He shows me several possible designs for his paper dresses and I am elated to be able to see the work in progress beforehand, to imagine these dresses worn at the exhibition by participants. I believe Syed does have the courage to continue to push boundaries and this is important because artists like him shine a harsh light on aspects of society that we often prefer to leave in the shadows. They are vital agents for societal reflection and ultimately for positive change.