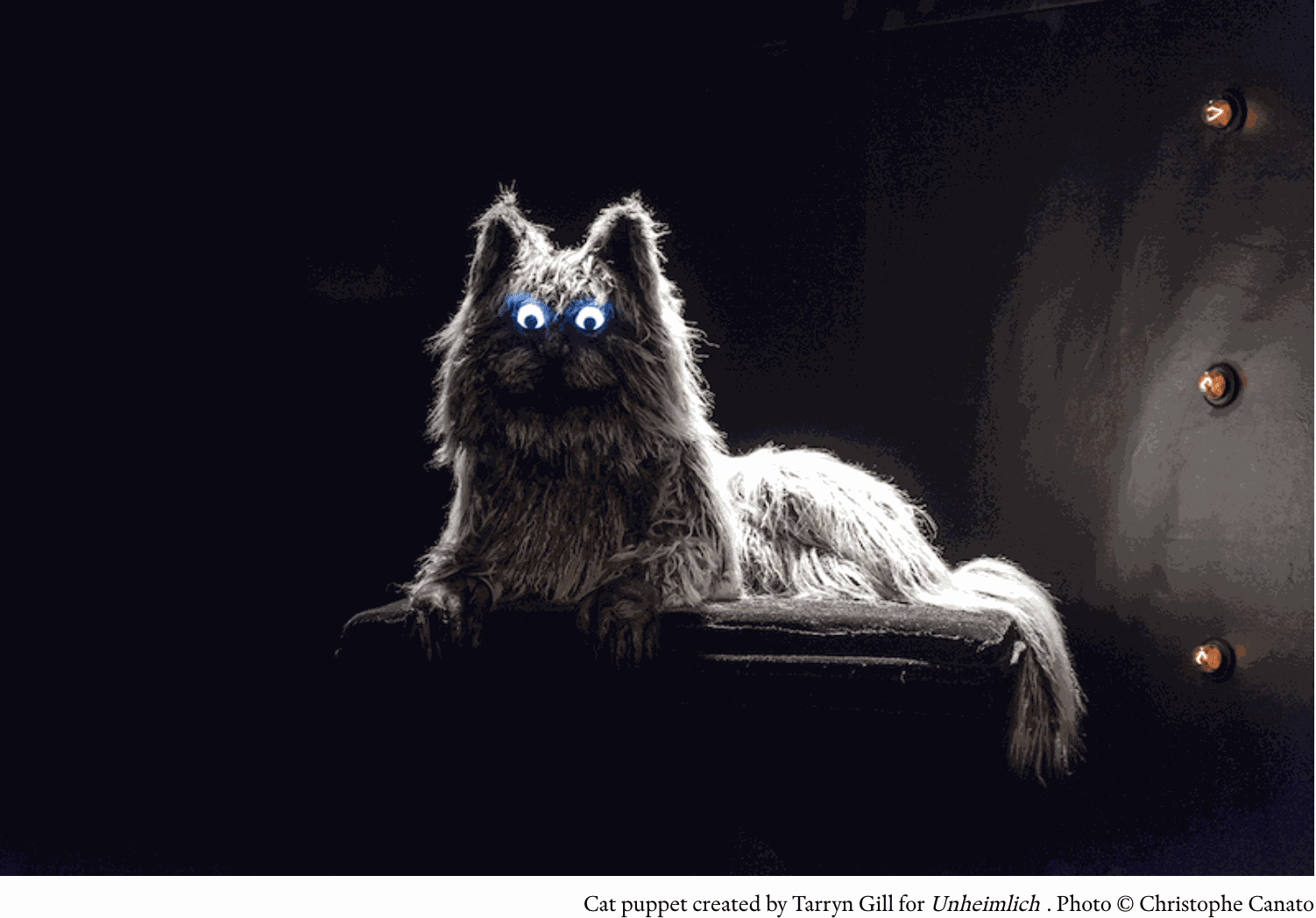

Upon closing my eyes after seeing Katt Osborne’s and Tarryn Gill’s wonderful interdisciplinary performance work Unheimlich, the spooky, giant cat-faced spirit from the show entered my dreams. The piece is enrapturing but also disturbing and it is certainly bleak. It presents, in an episodic, abstract fashion, the implosion of a couple, or more particularly the psychic and emotional breakdown of both parties. It is not for the faint-hearted, even if it is gorgeous in the use of light, colour, and various textures (woolly masks, hard tiles, etc). This is a series of unsettlingly beautiful sculptures rendered as an on-stage dreamscape.

Five principal artists are responsible to this very “unhomely” (as “unheimlich” translates) performance. Gill rendered the masks which serve as the inspiration for the show. Theo Costantino developed the text, which includes extended rants from a nasty cat-beast, as well as a series of basic interactions over a board game in which one is invited to identify faces and which then is recited again – either by both parties, or by one of them only, while the second is silent. Joe Paradise Lui’s lighting moves us from green tinged boudoirs which sparkle off the fabrics and set, to purple and red smoke-filled fantasias. Brett Smith’s soundscape is punctuated by hard, slamming cuts between scenes, typically filling out the space such that it always seems like there are others chattering in the wings and that voices are intruding into the stage space from elsewhere. And it is Osborne as the director who pulls this together and directs the performers.

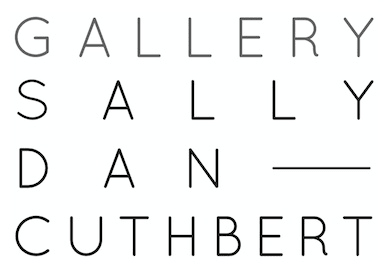

The cat’s main “human” (as it calls her) is played by Sarah Nelson; her own male “human” (as he calls himself) is Brendan Ewing. Rachel Arianne Ogle plays one of two non-speaking figures who present the scenes to us and to the on-stage humans, moving set items or offering their bodies for perusal or rejection. Jacob Lehrer plays the second of these, as well as the body of the cat, while voiceover from Igor Sas gives our monstrous narrator a compellingly nasty ocker drawl, which both seems to emanate from the beast, but also come from outside of it.

There are many ways one might read the performance, though the famous essay by psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud on the Uncanny is clearly at the heart of the production. As the Freud Museum’s website usefully summarises, Freud discusses hallucinatory fantasies of “inanimate figures coming to life”, “severed limbs” and image of one’s own “double” or “doppelgangers”, all of which appear within the production.

We are first introduced to the cat in the form of a spooky talking statue, which rests on the left of the stage throughout the performance, its eyes blinking when it speaks. As the male human begins to lose his way, he encounters a series of isolated and seemingly severed limbs, which come out of the curtains to tempt and embrace him (a direct quotation from Jean Cocteau’s landmark Surrealist 1946 film Beauty and the Beast). The woman is later entranced by an oversized primitivist green Graeco-Roman mask, which hovers about her, while the man later dons a similar shaggy, white masculine mask, becoming another person who is still, in some ways, the man also. Which of the two humans the cat doubles in the form of yet another oversized mask is anyone’s guess – perhaps both?

Freud contended that the Uncanny is that which is alarmingly familiar even though we don’t recognise it at first, and hence it seems threatening and unreal. It is something “unhomely” (unheimlich) which enters our memories of home and of comfort. For Freud, these unhomely things were repressed memories of our own childhood, of our early family life, parents, and of the acquisition of sexual knowledge. In this production however, the unhomely seems to arise less from forgotten or denied memories, but from fissures within each of the character’s sense of self.

The way the characters become deeply bonded to each other through repeated gestures and acts (notably a set of interactions around a bowl of cheezels), but then incomprehensibly but uncontrovertibly estranged from each other, suggests that at some level even lovers can never come to know each other, and hence that, at some level, part of one’s own partner remains disturbingly foreign to each of us.

But it is more than that. The complete breakdown of the characters – most visibly dramatised by a superb dance sequence where Ewing boogies to New Order’s Blue Mondayin sharp, funky poses while wearing the white mask – seems to arise from their own lack of knowledge and ease with their own selves. The unhomely then lies not just in the home, or in a relationship between lovers, but in oneself. It’s a pretty dark concept but this performance goes a long way to persuading me.

Such deep ruminations aside, the piece is a joy of image, sound and acting, harking back to early 20th-century avant-garde works such as Wedding Party at the Eiffel Tower (1921) and Parade (1917) – both of which were also by Cocteau – and The Breasts of Tiresias (1903), all of which dramatised bizarre combinations of human and the non-human entities and objects through the use of extraordinary moving sculptural costumes.

There is more of a conceptual and dramaturgical through-line to Unheimlich’s visual-art-meets-theatre approach than the fragmentary, jump cut ensembles of the early avant-garde. Moreover while Freudian sexology and Surrealism were clearly influences on Unheimlich as they were on Cocteau et al, ultimately this is not a piece about desire in the way that Surrealist art is. Unheimlich by contrast is a performatively and materially realised meditation on the nature of the self, and just how broken up, fractured and fucked up we can get – with or without the help of a demon cat mask!