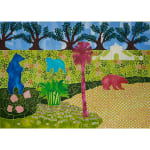

Fernando do Campo

Spring in the Schoolyard with Sun Bears, 2023

acrylic on canvas

153 x 204 cm

My practice is ongoingly concerned with the non-human histories that I encounter in the field and in the archive, and the potential to narrate these histories to ask critical questions...

My practice is ongoingly concerned with the non-human histories that I encounter in the field and in the archive, and the potential to narrate these histories to ask critical questions about our own human species. ‘Planting a World’ is a series of new large-scale paintings that consider the complex and often contrary ways that tree companions affect my relationship to place.

Trees have the capacity to thrive and become at home in locations where they may not naturally occur, arriving by wind, animal carrier, or human hand. As humans, we are aware of many introduced species around us, but the age and wisdom of trees and the fact we often can’t place their origins because we’ve encountered them across multiple locations before, means we construct a relationship with them in a slightly different way. At the same time, encountering a specific tree species can teleport us to another time and place, like hearing a song or the name of someone who has passed. Meeting a Weeping Willow (originally from Northern China) will always drag me back to my childhood home in Mar del Plata, Argentina; while Jacarandas will always be ‘Paddington in November’ for me, although native to South America. Trees are also witnesses to human behaviour and story across generations. The white gums at the Royal Botanical Gardens that pre-date colonial arrival; the 19th century date palm at Sydney Girls High that was planted with the establishing of Sydney Zoo – specimens that have witnessed ever-shifting socio-political and cultural seasons.

Narrating these complex tree histories also presents a particular invitation for me as painter. How can a ground/painting ground, be strong while unsettled; how can a shifting terrain be represented while constructed or emergent; are there painting languages carried by these trees across time through the history of their representation; what are the pictorial responsibilities of telling tree stories; are these tree paintings, portraits, landscapes, or narratives? ‘Planting a World’ alludes to the artifice of the post-anthropocentric environments which humans now traverse, constructed landscapes of multispecies relations, while also producing a space for a pluriversal tree story to be told, inviting knotty human-tree histories to be imagined.

Trees have the capacity to thrive and become at home in locations where they may not naturally occur, arriving by wind, animal carrier, or human hand. As humans, we are aware of many introduced species around us, but the age and wisdom of trees and the fact we often can’t place their origins because we’ve encountered them across multiple locations before, means we construct a relationship with them in a slightly different way. At the same time, encountering a specific tree species can teleport us to another time and place, like hearing a song or the name of someone who has passed. Meeting a Weeping Willow (originally from Northern China) will always drag me back to my childhood home in Mar del Plata, Argentina; while Jacarandas will always be ‘Paddington in November’ for me, although native to South America. Trees are also witnesses to human behaviour and story across generations. The white gums at the Royal Botanical Gardens that pre-date colonial arrival; the 19th century date palm at Sydney Girls High that was planted with the establishing of Sydney Zoo – specimens that have witnessed ever-shifting socio-political and cultural seasons.

Narrating these complex tree histories also presents a particular invitation for me as painter. How can a ground/painting ground, be strong while unsettled; how can a shifting terrain be represented while constructed or emergent; are there painting languages carried by these trees across time through the history of their representation; what are the pictorial responsibilities of telling tree stories; are these tree paintings, portraits, landscapes, or narratives? ‘Planting a World’ alludes to the artifice of the post-anthropocentric environments which humans now traverse, constructed landscapes of multispecies relations, while also producing a space for a pluriversal tree story to be told, inviting knotty human-tree histories to be imagined.